Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are the largest animals ever known to have lived on Earth. The Northeast Pacific is home to one of the world’s most studied blue whale populations, and Cascadia Research Collective has been a leader in understanding their distribution, behavior, and long-term movements for more than 40 years.

Size & Appearance

Blue whales can reach 80 – 100 feet and weigh up to 150 – 180 tons. Their long, slender bodies appear blue-gray underwater, and their tall, cone-shaped blow, often 30 feet high, is one of the most distinctive cues for identifying them at sea.

Life Span

Blue whales can live 70 – 90+ years, with some individuals estimated to surpass a century.

Diet & Feeding

Despite their enormous size, blue whales feed almost exclusively on krill, consuming several tons per day during peak feeding seasons. They lunge through the water to engulf vast swarms of krill before filtering from the water using the baleen plates lining their upper jaw.

The Northeast Pacific Population

The Northeast Pacific population migrates seasonally between winter breeding areas in Mexico and Central America and summer/ fall feeding areas from California to British Columbia. Cascadia’s decades of photo-identification and tagging studies have revealed consistent feeding hotspots along the US West Coast, including the Southern California Bight, Monterey Bay through the Gulf of Farallon’s, and waters off Northern California/ Southern Oregon.

This population remains endangered, with worldwide blue whale numbers still far below pre-whaling levels.

Blue Whale Quick Facts

Scientific name:

Balaenoptera musculus

Size:

80–100 ft (24–30 m)

Weight:

Up to 150–180 tons

Life span:

70–90+ years

Population status:

Endangered; still well below pre-whaling numbers

Where they occur:

California Current System (California, Oregon, Washington, BC)

Wintering areas off Mexico & Central America

Diet:

Krill (can consume 4+ tons per day)

Feeding method:

High-energy lunge feeding on dense krill swarms

Migration pattern:

Flexible, prey-driven movements along the US West Coast. Winter/spring breeding areas farther south

Main threats:

Vessel strikes, fishing-gear entanglement, ocean warming/krill shifts, noise, pollution

Cascadia’s role:

40+ years of photo-ID, tagging, abundance studies, health assessments, and management-focused research

Migration Along the US West Coast

Blue whales generally appear off the US West Coast from May through November, following dense krill patches influenced by oceanographic conditions.

Their migration is less rigid than gray whales; instead of a single corridor, blue whales track productivity and prey distribution, making them sensitive to climate-driven ecosystem shifts.

Threats to Blue Whales

Blue whales face several significant conservation challenges:

- Ship strikes, particularly in busy shipping corridors

- Entanglement in fishing gear

- Changes in krill distribution driven by ocean warming and climate variability

- Anthropogenic noise (shipping, military activities, seismic surveys)

- Chemical contaminants and pollution

- Historic population depletion from commercial whaling (still recovering)

Ongoing monitoring is essential to understand how blue whales are responding to rapidly changing ocean systems.

Cascadia’s Blue Whale Research

Cascadia Research Collective maintains one of the world’s most important long-term blue whale research programs, including:

- Photo-ID catalog spanning thousands of individual blue whales

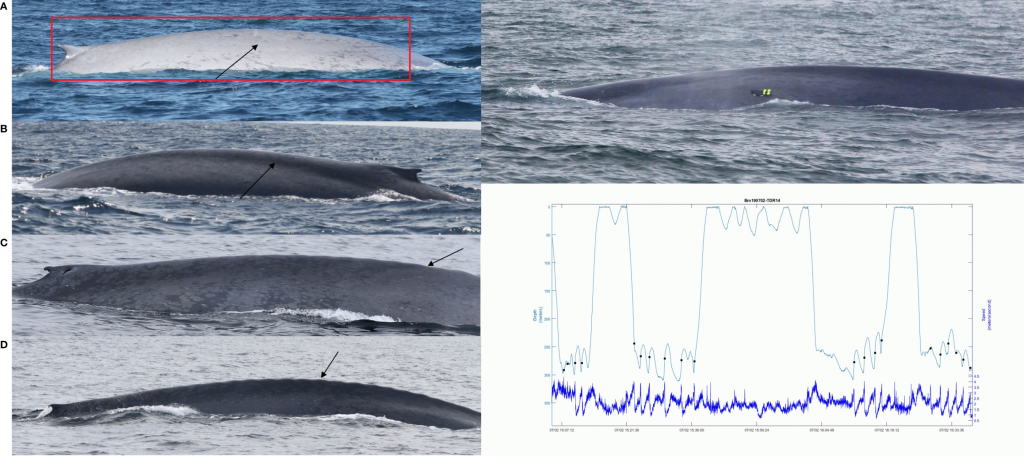

- Archival tagging to study fine-scale behavior and migration

- Long-term abundance estimates & population assessment

- Krill-prey mapping and relationships between ocean conditions and whale distribution

- Health and body condition studies using vessel based and drone documentation

- Ship-strike risk assessment

- Behavioral response studies

Cascadia’s data have directly informed regional management measures, including vessel speed restrictions and shipping-lane adjustments to reduce whale strikes. Click on the topics above to learn more about Cascadia’s diverse research.

Watch the video below from our collaborators at Stanford University talk about new technology to record the heart rate of blue whales. Cascadia and Stanford have continued to advance this science with new tag design in 2025 with further testing planned for 2026.