A group of bottlenose dolphins have been seen in Puget Sound since September, 2017. This is quite an unusual occurrence because bottlenose dolphins tend to live in warmer temperate and tropical waters and are not usually found in the colder waters of Puget Sound. With the help of members of the public, and dolphin researchers in California, Cascadia Research is able to confirm that this group of bottlenose dolphins are a part of the California coastal stock. After receiving a high quality photo of one of the animals, our colleagues in California were able to match the unique markings on the animal’s dorsal fin with images in their photo identification (photo ID) catalogs. San Francisco-based Golden Gate Cetacean Research (GGCR) and Monterey-based Okeanis identified the individual as “Miss”, a well-known dolphin first photographed by researchers in 1983.

A small group of dolphins appear to have traveled north from their usual habitat in northern California and entered Puget Sound sometime in September 2017, when the initial sightings were reported to Cascadia. Since then, members of the public and organizations including Orca Network, Orca Conservancy and a local whale watching company, Island Adventures, have all spotted the dolphins. A photo taken by an Island Adventures naturalist, Tyson Reed, in Hale Passage on November 4, 2017 showed one dolphin with quite unique notches on its dorsal fin. This photo was sent to researchers in California where it was compared to three different photo-ID catalogs and the animal’s identity was confirmed as “Miss”.

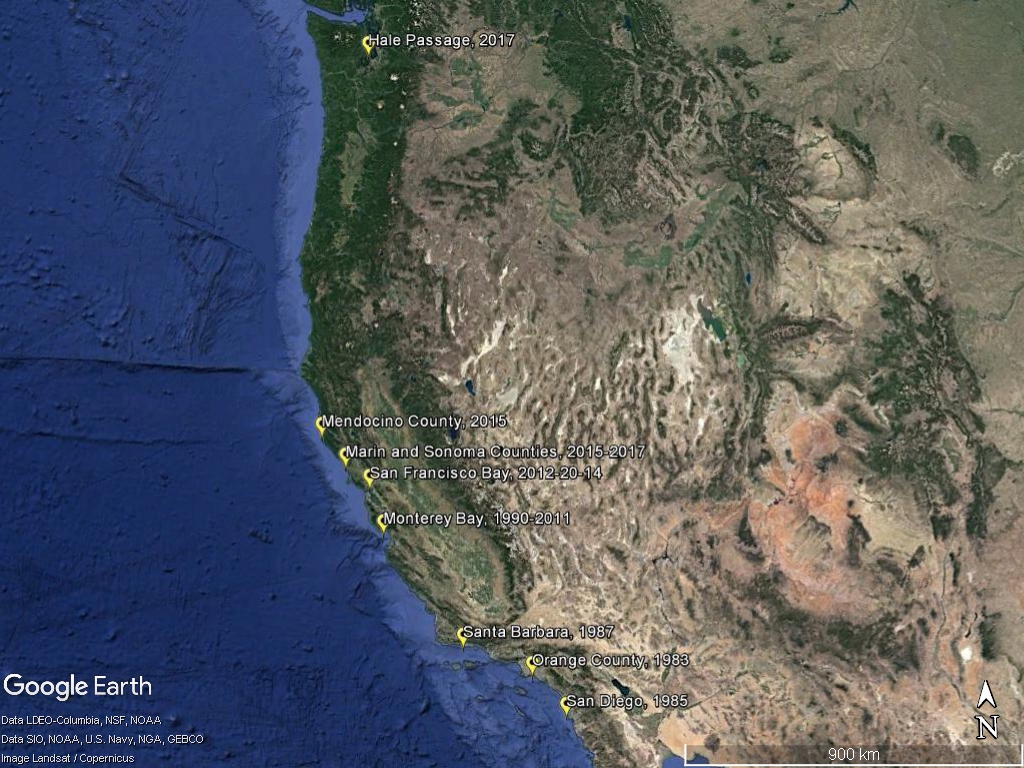

Miss was first observed in southern California in the 1980s. She moved to Monterey Bay in the 1990s and then to the San Francisco Bay Area in 2012. This is the first time that an individual bottlenose dolphin that has appeared in the Puget Sound has been traced to a specific population! It is unknown how many dolphins are part of this current influx, but we suspect that there are at least 5-6 individuals based on photographic evidence and the locations and timing of different sightings.

Miss has been around for quite a while, with the earliest sightings in 1983 in Orange County, almost 35 years ago. She was later sighted in San Diego in 1985 (NOAA catalog, pg 413, warning large 1300 page file), and Santa Barbara in 1987. These sightings were all within the traditional range of the California coastal bottlenose dolphin stock, but with the warm waters of the 1982 El Niño, animals started moving north of Santa Barbara.

During the early-1990s, Daniela Maldini of Okeanis sighted Miss numerous times during her Masters work studying the northern range expansion of this stock as they moved into the Monterey Bay area, where Daniela’s catalog from those early years show pictures of miss every year from 1990-1995). In fact Miss was one of the pioneers in the area, earning her the ID #2 in the photo-ID catalog for Daniela’s study area.

As the stock continued its northern expansion, Miss spent less time in Monterey Bay. In 2012 GGCR started spotting her in the San Francisco Bay, where she was seen several times over a period of two years. After 2015, she was only seen along the coast north of San Francisco, often pushing the limits of where members of this population are expected to be seen. According to Bill Keener of GGCR, Miss was seen as far north as Point Arena, Mendocino County, California in 2015, before returning south into Sonoma County, where she was last seen in late-March 2017. Around 6 months after this last sighting, Miss was one of the dolphins that showed up in the Puget Sound.

California coastal bottlenose dolphins

As with the different ecotypes of killer whales that we are familiar with in Washington (resident, transient and offshore), there are two ecotypes of bottlenose dolphins off the west coast of the United States (coastal and offshore). The coastal animals are generally smaller, a lighter grey, and stick to the warmer shallow waters near shore, while offshore animals are larger and usually darker grey, sometime appearing black.

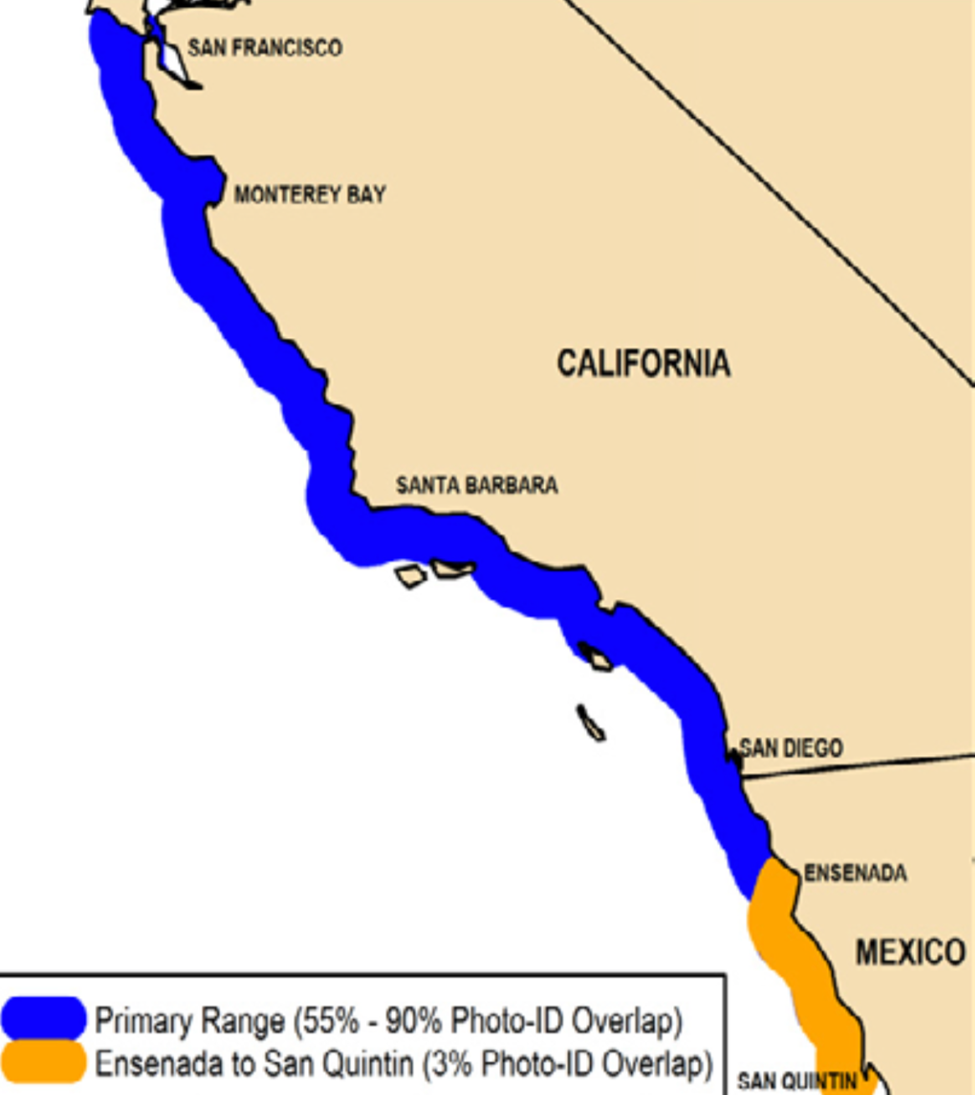

The California coastal stock of bottlenose dolphins is a genetically distinct population of about 500-600 animals that remain in a narrow corridor up to approximately 1 mile offshore between Ensenada, Mexico, and Sonoma County, California, just north of the San Francisco Bay. By using dorsal fin photos to track them, researchers have found that some individuals in this population can be highly mobile, engaging in long-distance movements north and south across their range in California. This stock has been expanding its range since the El Niño event of 1982, when they were rarely seen north of Santa Barbara. Sightings in San Francisco Bay began in 2001, where they are regularly seen today.

A continued northward expansion has been documented, moving into Marin and Sonoma Counties in 2012, and up into Mendocino County in 2015.

The sightings in the Puget Sound of several animals suggest a possible significant expansion of their range if they remain in the area, as the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca is almost 800 miles north of their range as defined by the current stock assessment report for this group of animals, and almost 1000 miles by water to get to the southern Puget Sound. Such long distance travel outside their traditional range may be due to long term changes in climate, and shorter term fluctuations in coastal water conditions, such as El Niño events. It is unclear whether the animals are here to stay, or if they are just here for a brief visit, as has happened in the past (1988, 1998, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011).

Three of the past bottlenose dolphins in the Puget Sound were later found stranded (1988, 2010 and 2011). All of the animals were genotyped, and with both coastal and offshore individuals showing up in the past. Whenever a species, such as these coastal bottlenose dolphins, are found so far outside their range, there are reasons to be concerned about their health. Animals may travel outside their normal range for many reasons beyond environmental change, such as confusion caused by disease or hunger, often leading to death of the animal. The earlier stranded bottlenose dolphins are an example of this, and there is cause to be concerned about at least one of the bottlenose dolphins in the current group that is suffering from a severe skin condition.

How Can You Help?

You can report any sightings of any dolphin species within the inland waters to Dave Anderson (danderson@cascadiaresearch.org). Clear photographs or videos of the animals are helpful for identifying species and the body condition. Higher quality images of the dorsal fin are also useful for identifying individual animals, and can be compared to catalogs from other areas. If you have a DSLR or point and shoot camera with a good zoom on it, consider bringing that on your trips out onto the water or to the beach, as the improved detail in the images is helpful in identifying the animals.

Remember that dolphins are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recommends that boaters and paddlers maintain a 300-foot distance to prevent harassment.