Cascadia Research has been collaborating with the Northwest Fisheries Science Center of NOAA Fisheries, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, to examine aspects of the diet of fish-eating “southern resident” killer whales, and to study sub-surface behavior of mammal-eating “transient” killer whales. For the last four years we’ve spent ~4-5 weeks per year based out of the Friday Harbor Labs on San Juan Island undertaking field work. From September 8th through the 22nd 2008 we’ll be based in Friday Harbor again undertaking field work.

Cascadia Research has been collaborating with the Northwest Fisheries Science Center of NOAA Fisheries, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, to examine aspects of the diet of fish-eating “southern resident” killer whales, and to study sub-surface behavior of mammal-eating “transient” killer whales. For the last four years we’ve spent ~4-5 weeks per year based out of the Friday Harbor Labs on San Juan Island undertaking field work. From September 8th through the 22nd 2008 we’ll be based in Friday Harbor again undertaking field work. Depending on what groups of whales are in the area, we have a number of goals:

- collecting fecal samples from “southern resident” and “transient” killer whales, to examine diet, as well as for hormone analyses undertaken by Katherine Ayres of the University of Washington. More information on this work is available on our killer whale diet web page

- collecting prey samples from both types of whales to examine diet

- deployment of suction-cup attached time-depth recorders (some with the ability to record sounds) on both types of whales, to examine sub-surface and acoustic behavior. More information on the suction-cup tagging work is available on our killer whale diving behavior web page

- deployment of medium-term satellite tags on “transient” killer whales (attached with darts to the dorsal fin), to examine movements over periods of weeks to months. We’ve been using these types of tags on five species of toothed whales in Hawaiian waters, with attachment durations of up to 72 days. For more information on this work see this page.

- collecting a small number of biopsy samples to examine toxin loads in both fish-eating and mammal-eating killer whales, carrying on analyses originally reported by Krahn et al. in 2007

- opportunistic collection of identification photographs and biopsy samples from minke whales. Photos will be contributed to the Northeast Pacific Minke Whale Project while biopsy samples will be analysed by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center for toxins and stable isotopes.

- collect sighting information on other species of cetaceans in the area.

We’ll post updates and information on this work every few days during the field project. The most recent updates are at the bottom of the page.

|

Approaching a fluke print on our first day on the water, with a new research vessel, the NOAA R/V M1. The R/V M1 is a 21′ Hurricane, replacing the 19′ R/V Phocoena used in previous years. The vessel is named after the “transient” killer whale M1 (aka Charlie Chin, aka T1), one of the most recognizable killer whales that used to be found in these waters (M1 died a number of years ago). Photo by Ken C. Balcomb, Center for Whale Research. Greg Schorr, from Cascadia Research, is on the bow platform with a swimming pool net on an extendable handle to scoop samples (prey or fecal samples) left behind by the whales. The yellow flag flown on the boat is an indicator that we are working under a NMFS Scientific Research Permit (Permit No. 781-1824 issued to the Northwest Fisheries Science Center). |

|

Our standard operating procedure, following one or two killer whales (in this case J1, an adult male) from directly behind, allowing us to collect both prey samples and fecal samples, by checking each fluke print. Photo by Ken C. Balcomb, Center for Whale Research. |

|

Photo by Ken C. Balcomb, Center for Whale Research. |

|

A mammal-eating “transient” killer whale mother and infant off Sidney Island, September 12, 2008. Photo by Candi Emmons, Northwest Fisheries Science Center. On September 12th we encountered our first group of “transient” killer whales for the trip, with seven whales present (the T30s and the T46Bs). Note the orange coloration of the infant, typical of very young calves. |

|

A mammal-eating killer whale high-speed swimming off Sidney Island, September 12, 2008. Photo by Robin Baird. The two sub-groups had been apart when the T46As began high-speed swimming for ~20 minutes, eventually joining up with the T30s, who were carrying part of a large marine mammal (possibly a large seal or sea lion). |

|

Deploying a suction-cup attached “B-probe” (a Burgess Bio-acoustic probe) on J41, September 12, 2008. Photo by Candi Emmons. These tags, previously deployed on several other species of whales including blue, fin, humpback and pilot whales, record depth, pitch and roll, and acoustics, both sounds produced by the whales and other sounds in the environment. This tag only stayed on the whale for a few minutes before floating to the surface. |

|

An L-pod whale breaching near Deception Pass, September 13, 2008. Photo by Greg Schorr. |

Researcher Russ Andrews (of the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the Alaska SeaLife Center) and colleagues recently published a paper using remotely-deployed satellite tags to examine movements of killer whales in the Antarctic (a copy of their paper can be downloaded here), and researchers in Alaska are also using them to study movements of both fish-eating and mammal-eating killer whales. We have been using these same tags to study movements of cetaceans in Hawaiian waters (see more information here), and on September 15, deployed two of these tags on mammal-eating killer whales in Juan de Fuca Strait, to examine their movements. From our Hawaii studies, these tags have lasted an average of 36 days (maximum 72 days), so may give information on movements over a very large scale.

Mammal-eating killer whales are important top predators in the North Pacific. In recent years there has been a great deal of debate on the role these whales play in influencing their prey populations, particularly in Alaska. Understanding the movements of these animals is a critical component to assessing their influence on prey populations. Consequently, like researchers in Alaska we are deploying satellite-linked transmitters to determine whale movements. An understanding of large scale movements will compliment our time depth-recorder deployments, which provide fine scale subsurface behavior.

|

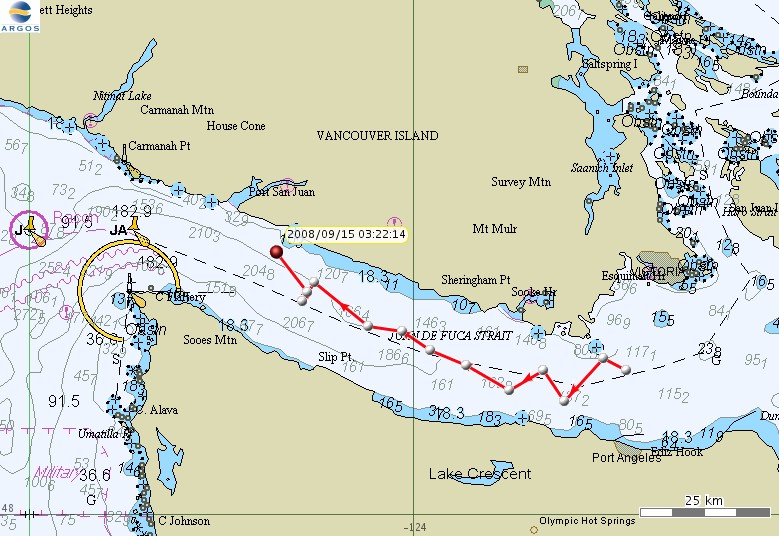

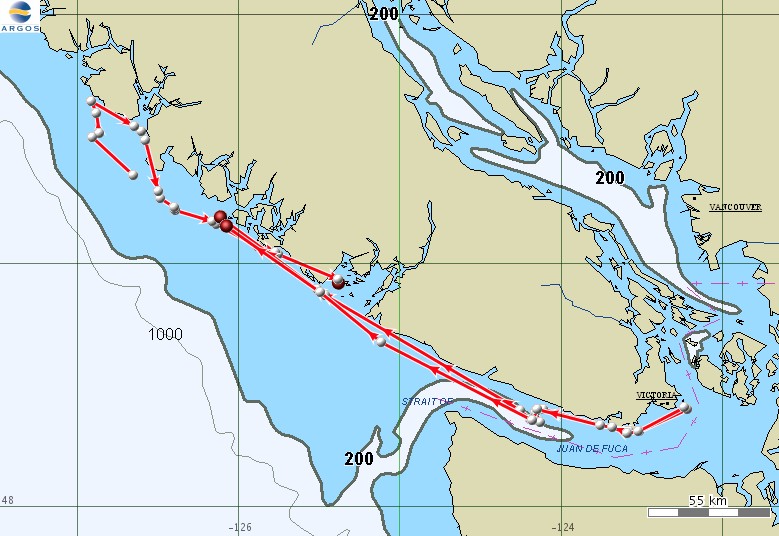

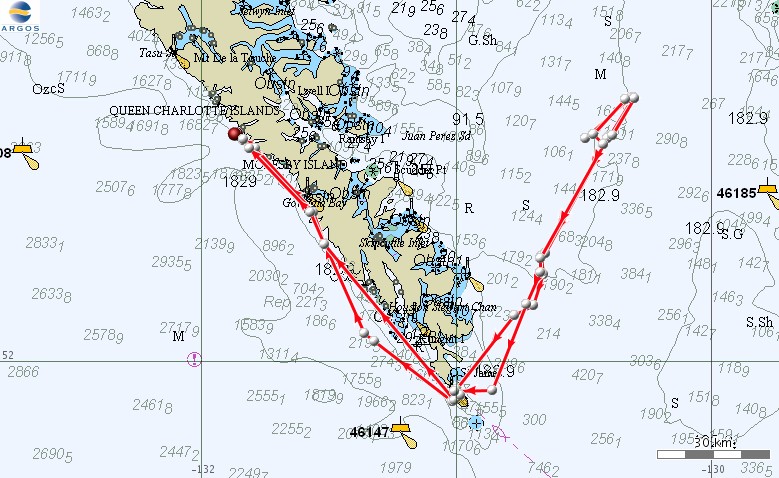

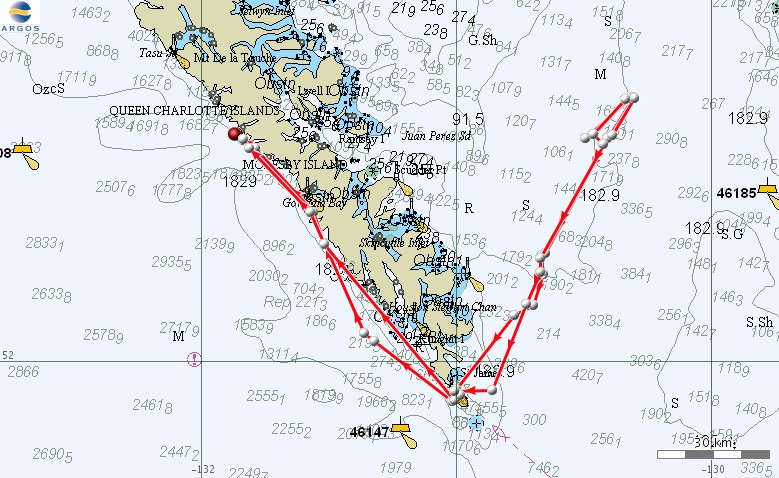

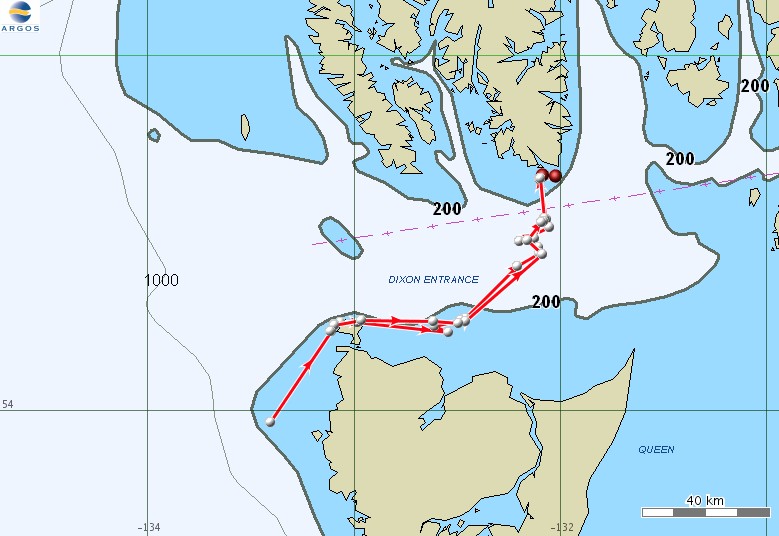

Overnight movements of mammal-eating killer whale T30A (aka P3), a 15-year old male. T30 (aka P2), T30A’s mother, was also instrumented with a satellite tag on September 14, 2008. |

|

“Transient” killer whale T30A with a medium-term satellite tag (visible on the trailing edge of the fin about 1/4 of the way up the fin), September 14, 2008. Photo by Greg Schorr. |

|

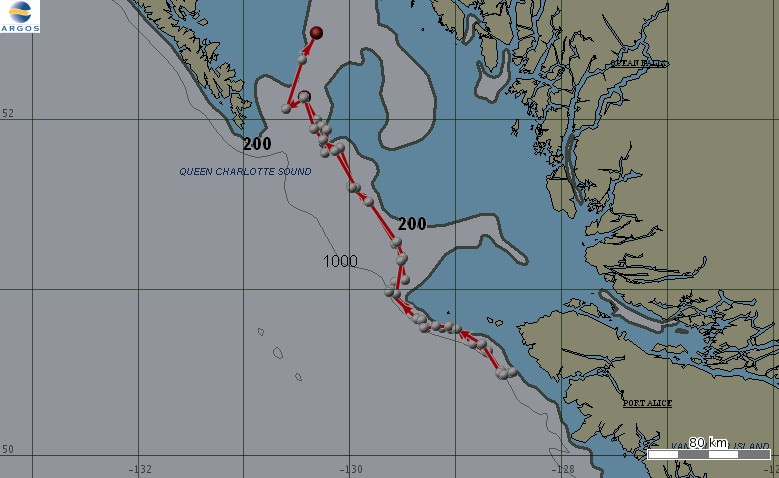

Movements of mammal-eating killer whale T30A in the day and a half since tag deployment. |

|

On September 16th we encountered a group of four mammal-eating killer whales (T18, T19, T19B, T19C) and were able to deploy a satellite tag on T19B, an approximately 13 year old male. The tag is visible in this photo on the right side of the fin near the trailing edge, approximately 40% of the way up from the base of the fin. Photo by Candi Emmons. |

Wondering why there are gaps in the tracks of our tagged whales?

In order to save on battery life, our satellite tags are programmed to transmit for 12 hours each day, during periods that correspond to the greatest number of ARGOS satellite overpasses. The tags have a salt-water switch, so only transmit when they are above the water’s surface, and have a minimum interval between transmissions of 30 seconds. The tags are set to transmit up to 500 times per day, but in order to obtain a location from the ARGOS system, the tag must transmit multiple times as the ARGOS satellite passes overhead, and the quality of the location (how accurate it is) largely depends on how many “hits” to the satellite the tag gets during a particular satellite pass (which only lasts 8-14 minutes). Some locations are very high quality (probably within a few hundred meters), whereas others may be accurate only +/- many kilometers, but still give a good idea of the general travel routes and habitat use.

We receive the location information once a day in the form of an e-mail from ARGOS, and can also access it on-line, although there is a delay (anywhere from 45 minutes to several hours) before the information is available on-line, so it is not particularly useful in locating the whales on a day-to-day basis.

|

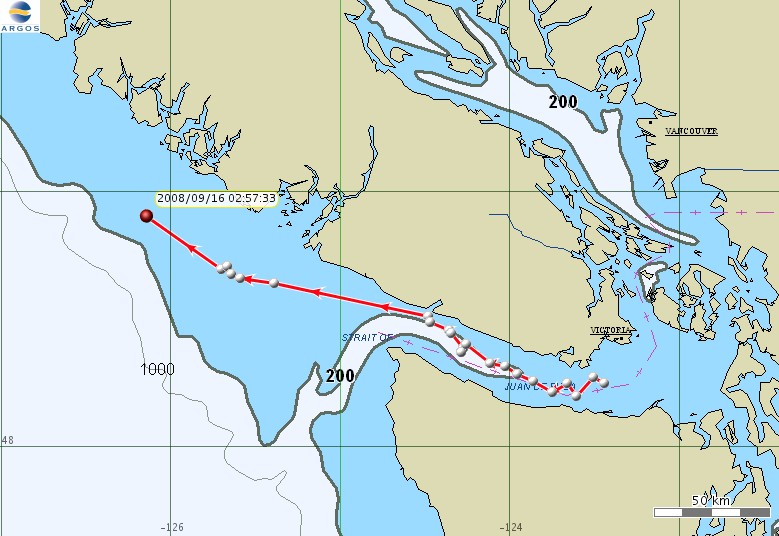

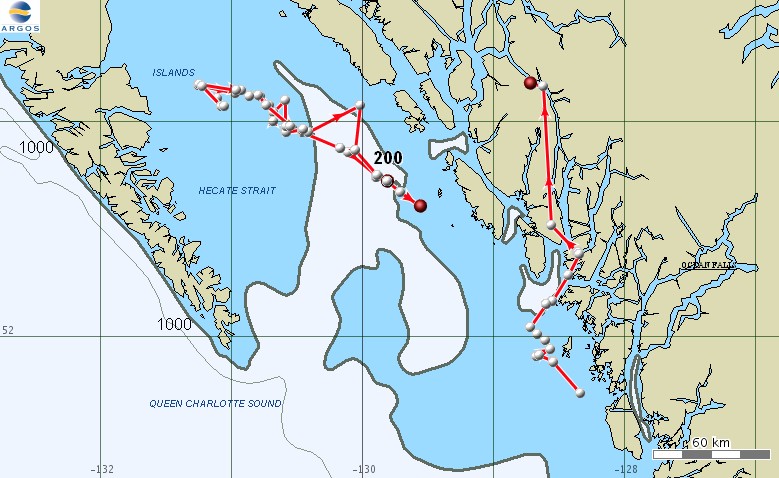

Movements of mammal-eating killer whales T30A (to the west) and T19B (to the east, tagged September 16) from mid-day September 16 through the morning of September 17. |

|

Movements of mammal-eating killer whales T30A (coming from the west) and T19B (coming from the east) from the evening of September 16 through the morning of September 18. |

On September 18 we had a productive day following individuals in J and K pods, collecting samples from three predation events. Meanwhile, T19B, who we tagged on September 16, spent the day offshore of Barkley Sound off the west coast of Vancouver Island (see map below).

|

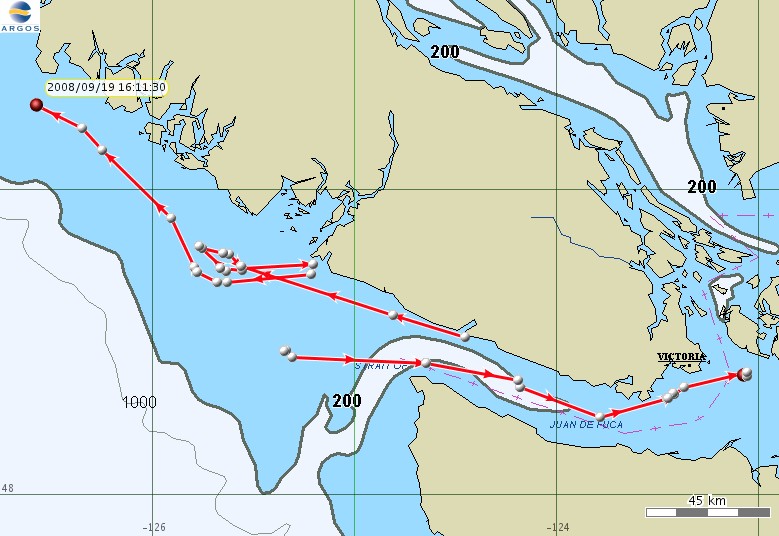

Movements of mammal-eating killer whales T19B (heading west) and T30A (heading east) from September 17 through the afternoon of September 19. |

Do we know exactly where the whales are all the time?

While the short answer is “no”, some background on how the Argos satellite system works is needed to explain this. Firstly, this system functions very differently than the Global Positioning System (GPS) most people are familiar with, and the Argos satellite system is not a simple or very accurate system. The transmitter on the whale emits a signal only when the whale is at the surface and only during a few specific hours a day when the transmitter is programmed to be on. In addition, the signal the transmitter emits can be received only by System Argos receivers which are only on NOAA’s polar orbiting weather satellites. Weather satellites orbit overhead about every 90 minutes, are overhead for only about 8-14 minutes and are generally most directly overhead during the morning hours to give weather forecasters a first look at cloud cover and/or environmental data the satellites collect. Assuming the satellite is overhead when the tag is turned on and the whale is at the surface, several signals are sent by the transmitter (each of which may be degraded by several factors, such as water on the antenna) to the satellite receiver. Assuming these transmissions are received (the transmitter produces a quarter watt signal that has to be detected by a satellite 800 miles above), these signals are then sent to a ground station which sends all the transmitter ID and frequency information to Argos headquarters in France for processing. Getting an estimated location requires the emission and receipt of a series of signals from a very stable frequency of the transmitter, and using a principle known as Doppler shift (this is what occurs when you hear a train horn sounding lower at the instant it passes by) a series of algorithms are applied to the signal data to estimate the transmitter signal’s location. Each location we receive has a location quality rating which estimates the amount of error associated with it. Argos has 7 location quality ratings, 4 of which have no error estimate associated with it – in other words the location may be correct or may be off by dozens of miles, usually the latter. Even for the 3 ratings that have error estimates assigned to them the actual locations can be off by up to a couple of miles. As might be expected we receive many more low quality locations than high quality locations. We typically only receive one or two high quality locations per day. In addition, the intial location that is received is preliminary such that additional post-processing that is conducted may significantly change the location. Unfortunately, this post processed information is not available from Argos for a month. Determination of the final set of locations requires the use of a filtering program to select those points that have the highest probably of being correct, based in part on the speed between consecutive locations. Consequently, of the numerous locations initially received each day only a couple might be considered reliable and even those are subject to having an associated error of several miles.

|

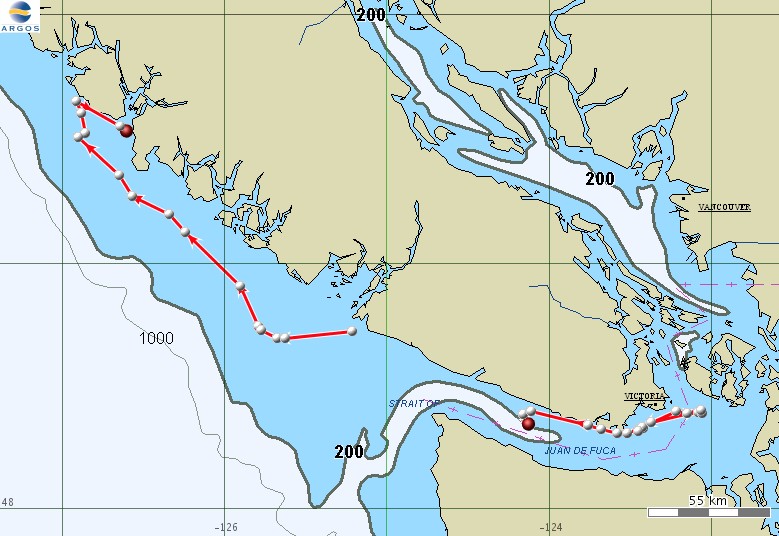

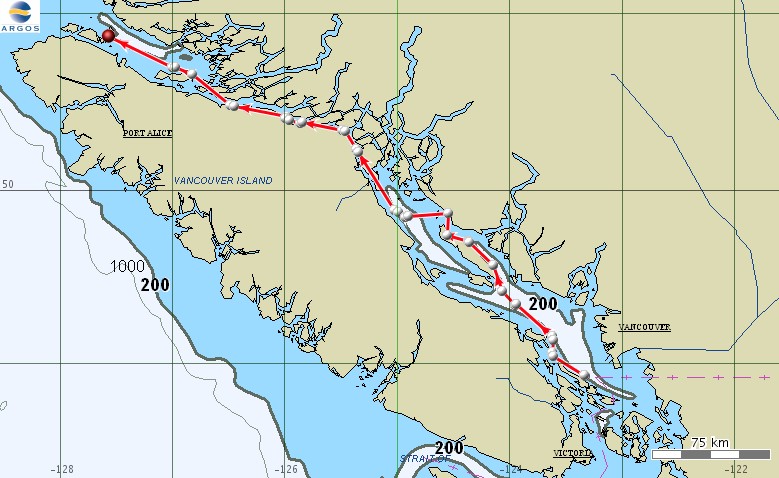

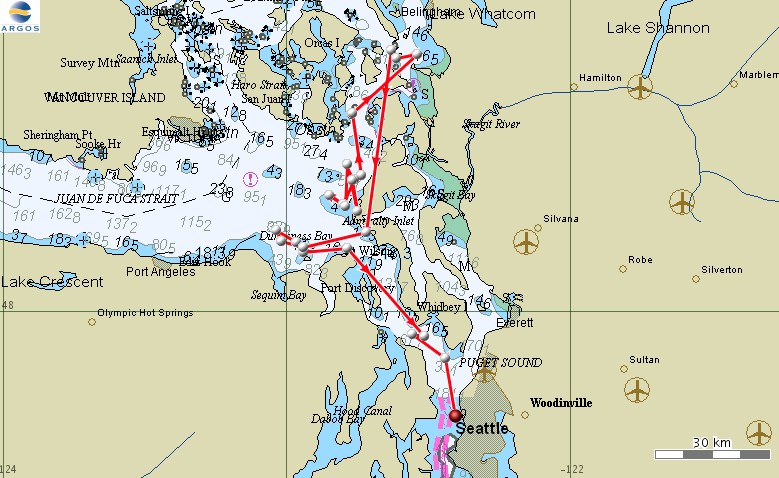

Movements of mammal-eating killer whales T19B (to the west) and T30A (to the east) from the evening of September 18 through the morning of September 20. |

|

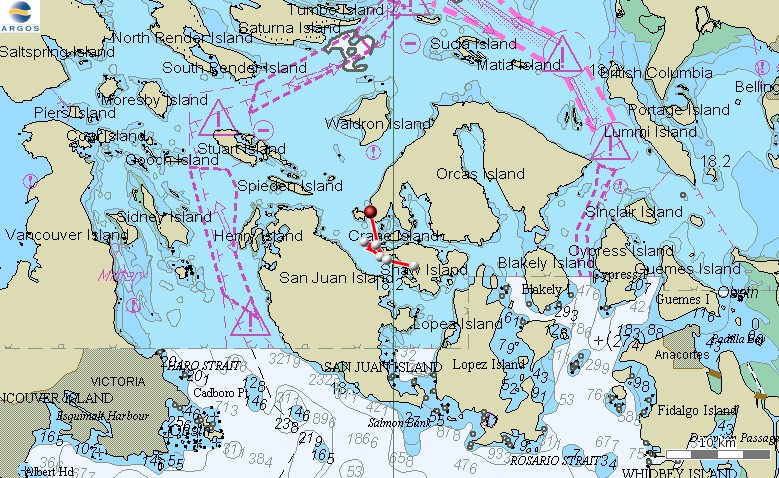

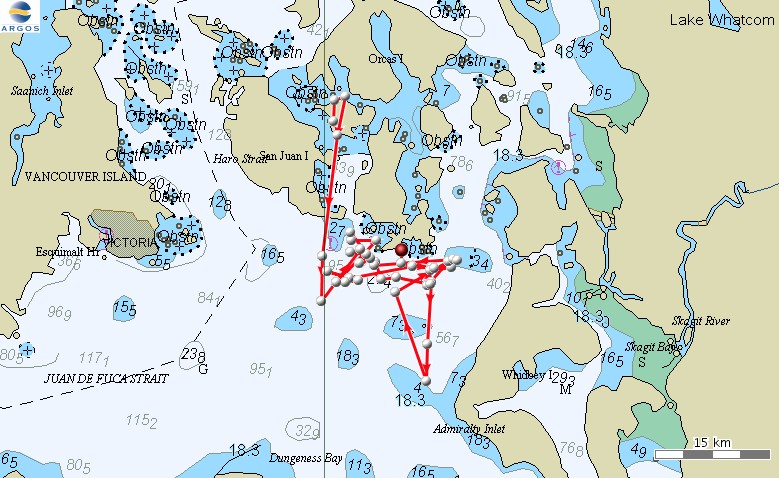

Movements of all three satellite tagged mammal-eating killer whales, from the afternoon of September 19 through the morning of September 21st. The two points together to the west (northwest of Tofino) are T30 and T30A (we’ve only been showing one of these at a time on previous maps to reduce clutter), while T19B is in Barkley Sound. |

|

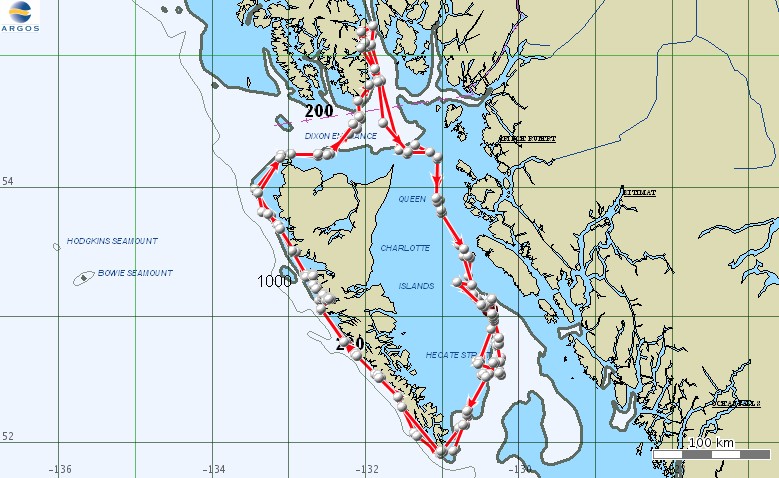

Movements of satellite tagged mammal-eating killer whales from the evening of September 20 through the morning of September 22nd. The T30s are continuing to move northwest along the west coast of Vancouver Island while the T19s are returning to inland waters. |

September 23 update

Our last day on the water was Sunday September 21st. We encountered a very cooperative minke whale, and were able to deploy a medium-term satellite tag to monitor movements (see the first map below). There is a small population of resident minke whales in this area that have been studied by Jon Stern, Rus Hoelzel and others (see the website of the Northeast Pacific Minke Whale Project), but little is known of their movements when they leave the inside waters.

|

Minke whale surfacing off Yellow Island, San Juan Channel. Photo by Robin Baird. |

|

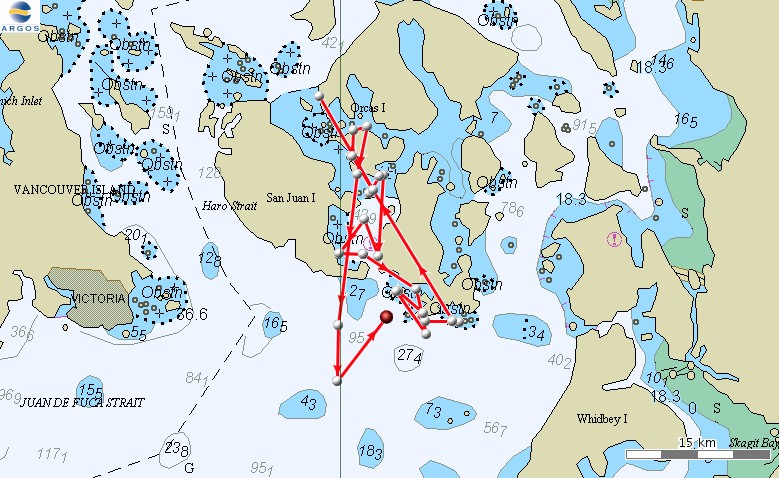

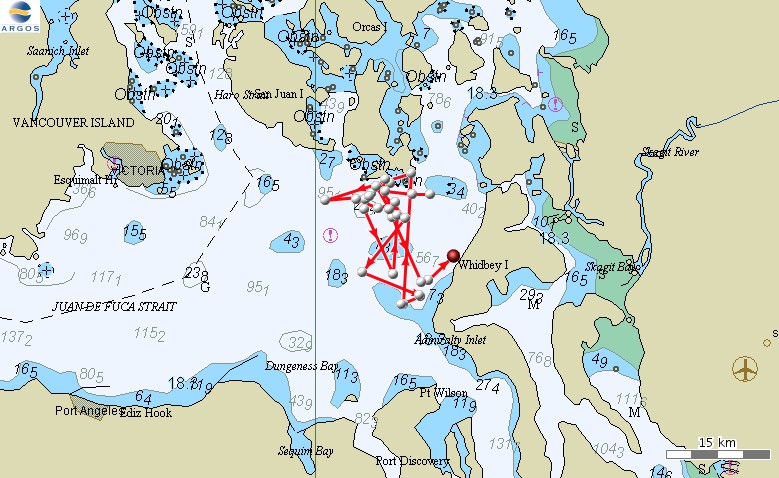

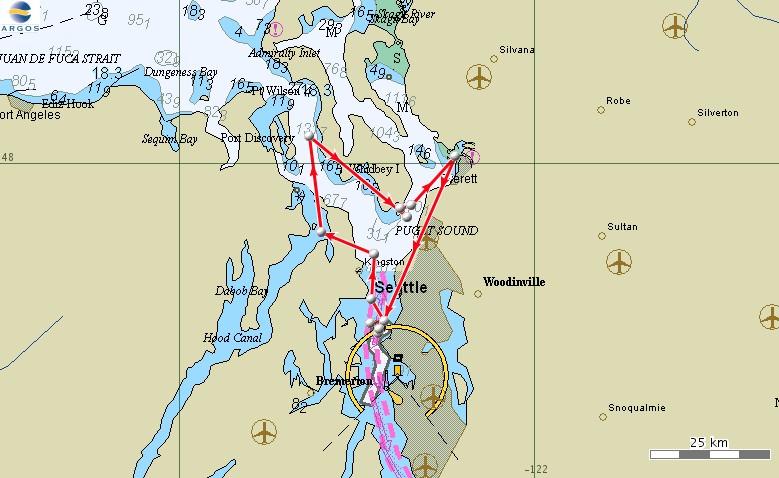

Movements of a satellite tagged minke whale from September 21st through the morning of September 23rd. |

|

Minke whale with satellite tag. Photo by Robin Baird. |

Minke whale IDd by Jon Stern and Frankie Robertson

The minke whale we satellite tagged on Sunday was IDd by Jon Stern and Frankie Robertson of the Northeast Pacific Minke Whale Project as an individual documented for the first time in the area in 2008 (in August off Hein Bank). When seen in August it was lunge feeding and showed some curiosity in their boat, as it did when we encountered it on Sunday. Frankie named the whale “Ellie”, after Ellie Dorsey, the pioneer of minke whale research in the area. The whale has a healed notch on the peduncle (visible in the photo below), as well as scarring around the notch probably caused by an entangled rope.

|

Minke whale with peduncle notch visible. Photo by Robin Baird. |

Marine mammal eating killer whales

|

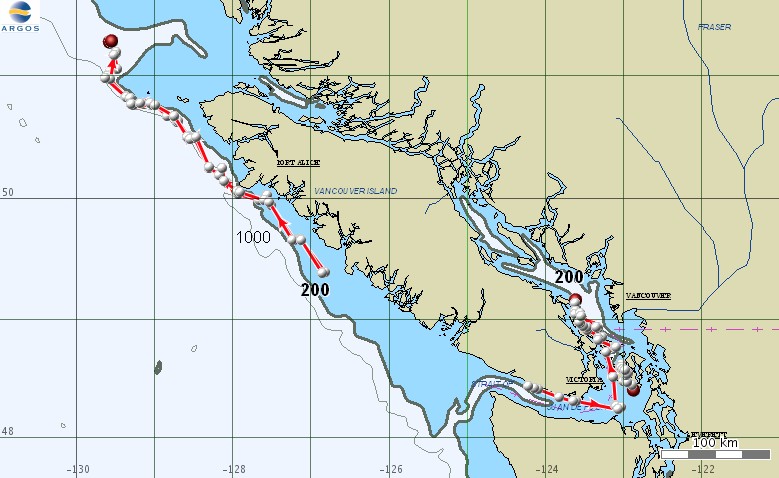

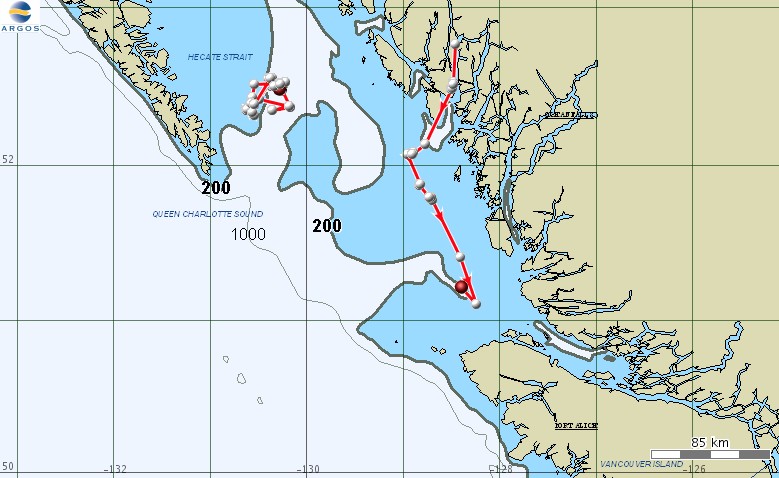

Movements of all three satellite tagged mammal-eating killer whales, and the satellite tagged minke whale, from the evening of September 21 through the evening of September 23rd. The T30s are generally heading towards the Queen Charlotte Islands. |

|

Two days of movements of the T19B and the satellite tagged minke whale, as of the morning of September 25. |

|

Two days of movements of the T30s as of the morning of September 25. |

|

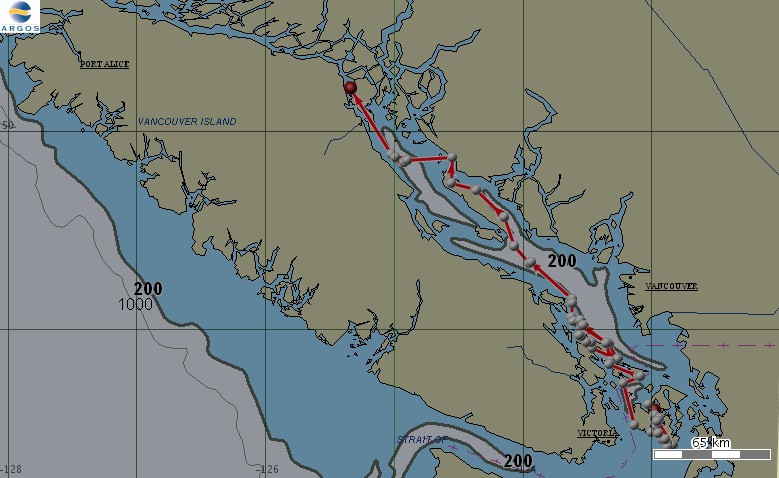

Movements of the T19s from the evening of September 23rd through the morning of September 26. During this time they covered at least 392 km over a 61 hour period. |

|

Movements of the satellite tagged minke whale from midnight September 22nd through the morning of September 26. |

|

Movements of the T30s from the evening of September 24th through the morning of September 26. Note the gap in the line between the two whales doesn’t necessarily mean they were traveling apart, but more likely reflects the different timing of the locations for the two individuals. |

|

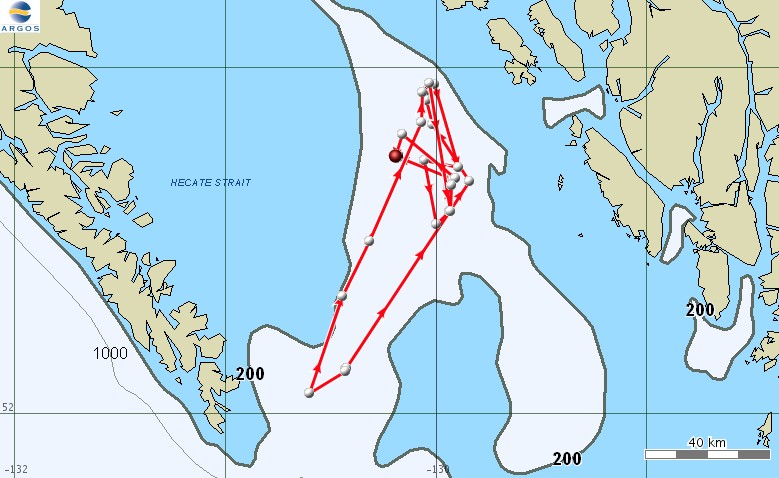

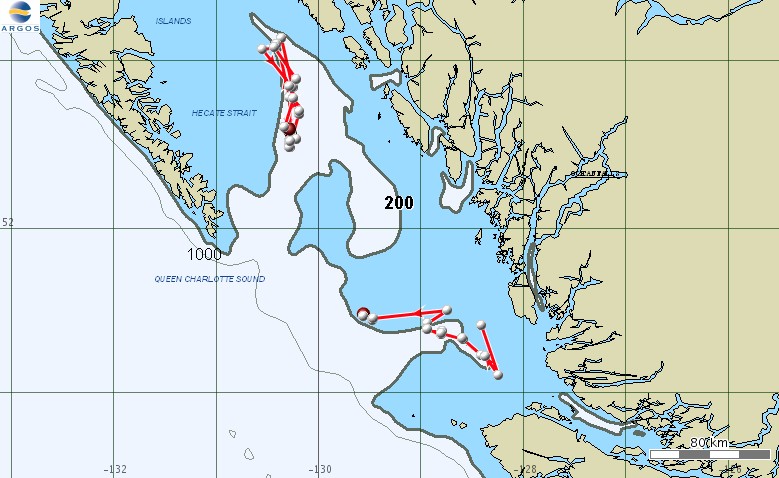

Movements from the evening of September 25th through the morning of September 27. The T30s have moved north in mid-Hecate Strait while the T19s have left Vancouver Island and are heading north in Queen Charlotte Sound. |

|

Movements from the evening of September 26th through the morning of September 28. The T19s are entering Milbanke Sound. |

|

Movements from the evening of September 27th through the morning of September 29. The T19s are traveling north in Princess Royal Channel. |

|

Movements from the evening of September 28th through the morning of September 30. The T19s turned around and retraced their route and both groups are back in southern Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound |

|

Movements of the satellite tagged minke whale from the evening of September 24th through the morning of September 30. |

|

Movements of the T30s and the T19s from the evening of September 29th through the morning of October 1st. |

|

Movements of the T30s and the T19s from the evening of September 30th through the morning of October 2nd. |

|

Movements of the T30s and the T19s from the evening of October 1st through the morning of October 3rd. |

|

10 days of movements of the T30s, through the morning of October 4th. |

|

10 days of movements of the T19s, through the morning of October 4th. |

|

Movements of the T19s from the evening of October 3rd through the morning of October 5th. |

|

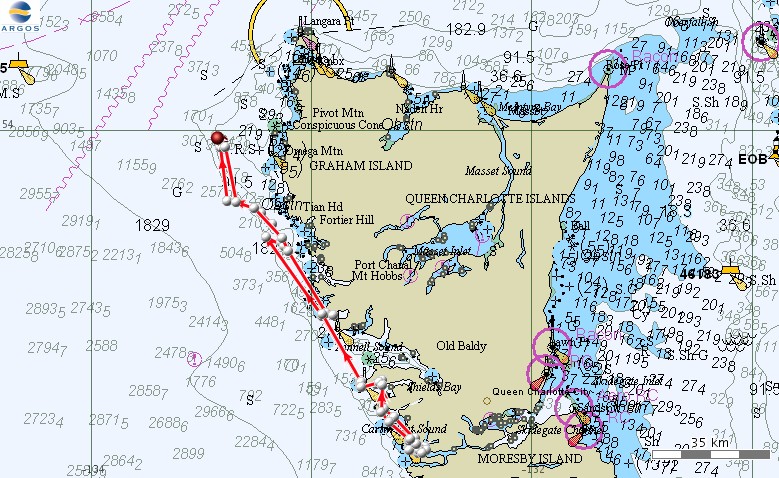

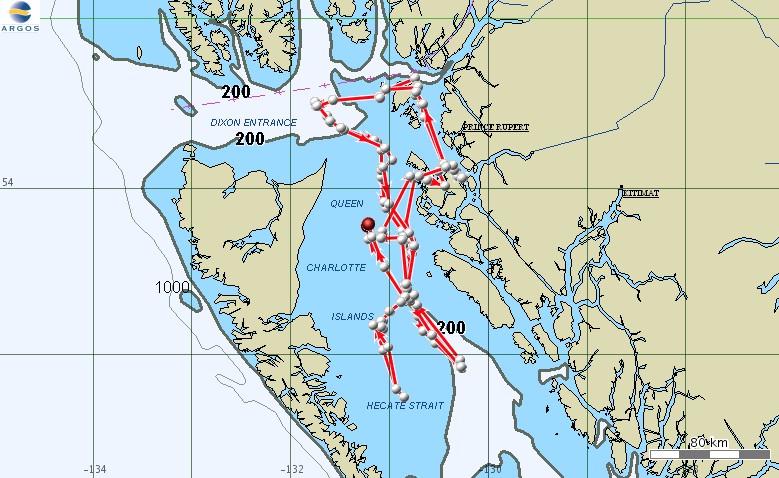

After spending 10 days in the open water of Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound, the T30s start to travel north along the west coast of the Queen Charlotte Islands. The map shows movements from the evening of October 3rd through the morning of October 5th. |

|

The T30s heading east in Skidegate Channel, between Moresby and Graham Islands. The map shows movements from the morning of October 5th through the morning of October 6th. |

|

The T19s heading southeast into Queen Charlotte Strait. Movements of the T19s from the evening of October 4th through the morning of October 6th. |

|

Movements of the satellite tagged minke whale from September 30th through the morning of October 6th. |

|

The T30s spent October 6 and most of October 7 in the west end of Skidegate Channel, and then started heading north along the west side of Graham Island the evening of October 7. The map shows movements from the evening of October 6th through the evening of October 8th. |

|

The T30s move into southeast Alaska. The map shows movements from the evening of October 7th through the evening of October 9th. |

|

The T30s spent only 1 day in southeast Alaska before moving back south through Hecate Strait. The map shows movements from the evening of October 8th through the morning of October 12th. |

|

Movements of the satellite tagged minke whale from October 6th through the evening of October 12th. This map includes all location quality hits from the satellite tag, so there is considerable uncertainty associated with some locations. |

|

Ten days of movements of the T30s, through the morning of October 14th. |

|

After spending several days in southern Hecate Strait the T30s appear to be traveling again, heading west in Queen Charlotte Sound. This map shows from the morning of October 15th through the morning of October 16th. |

|

Movements of the satellite tagged minke whale from October 12th through the evening of October 18th. This map includes all location quality hits from the satellite tag, so there is considerable uncertainty associated with some locations. |

|

Movements of the T30s from the evening of October 15th through the evening of October 18th. On the morning of October 17th the T30s made a brief stop in Juan Perez Sound, between Ramsay Island and Moresby Island, before heading back out into Hecate Strait. |

|

Movements of the T30s from the evening of October 17th through the afternoon of October 23rd. |